In 1847 a doctor digging his fingers into your wound probably wouldn’t have bothered to wash his hands. You might have died because he lacked a basic understanding of germ theory (that took a few more decades to catch on). It’s horrifying to ponder but that’s about the current level of practice in most Agile transformations today.

Even with thousands of books, countless conferences and blogs, and an explosion of certifications the fundamental nature of the problems we are paid to help solve are poorly understood at best and completely opaque to most. In short, many in our profession are like the physicians of old; sincere in their desire to help but applying leaches where antibiotics are required.

That’s why I almost never describe myself as an ‘Agile coach’ anymore; the eye rolls and looks of disgust are laughably predictable and for good reason; a lot of harm has been done to good people in the name of ‘Agile’ and ‘SAFe’. In my eighteen years as an ‘Agile coach’ I’ve done my share of harm and it’s all so unnecessary.

But what if there were a germ theory of Agile transformation? What if we deeply understood the nature and forces at work in organizations to such a degree that the next step we needed to take was almost ridiculously obvious?

Such a theory exists, in parts, but it’s just not yet cohesive, well known, or understood. It’s buried in (and obscured by) glib admonitions to ‘be servant leaders’ or ‘be agile’ that clarifies not the slightest what actually needs to be done. This journal is my first attempt to shed some light on this as a cohesive model both to help and to attract collaborators to expand on it because, without a germ theory of the problems we’re helping to solve, we will continue to do harm that can be avoided.

A Cohesive Germ Theory of Transformation

Parts of what I’m about to share here have been bubbling around in my head for close to a decade. I’ve shared some of it at conferences and in user groups but even I was struggling to reason around it and apply it consistently. Now, however, it’s come together in a way I think I’m ready to share because it’s changed everything about my practice. It informs every step, every decision, every interaction and the impact has been massive; a step function improvement in my ability to help others.

Parts of this will be familiar to many of you but it’s the practical application of these parts as an interdependent whole that provides the value. I’ll do my best to expand on these concepts and tie the elements together over my next set of journals.

In the meantime I’d like to get this ‘out there’ for discussion. I’ll share the ‘tip of the iceberg’ of this germ theory of Agile transformation in terms of some simple advice. These are the surface elements more easily understood without going too deep into the underlying principles that inform them. Consider this then as a teaser; a hint of what is to come.

The first five items serve as principles that form the nucleus of this germ theory of transformation. Again, this is just scratching the surface but I hope it will do for now.

- Transformation is a VUCA Problem: “What do you know about VUCA?” is the second question out of my mouth when I meet a client (after, “why am I here?” VUCA is a an acronym for Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, Ambiguous. Middle East problems are VUCA problems. Eradicating Ebola is a VUCA problem. Avoiding financial collapse is a VUCA problem and most Transformations are fundamentally VUCA problems. Strangely, VUCA remains a vague and foreign concept to most people yet its the fundamental nature of every non-trivial Agile transformation. This goes beyond just the Cynefin framework or the Stacey diagram glibly trotted out in Agile 101 discussions. Understand VUCA. Make sure your clients understand it too.

- VUCA Problems require an incremental approach: Only a highly adaptive and incremental approach to change works well with VUCA problems, thus successful Agile transformation requires an iterative, incremental, and adaptive Agile approach to succeed. Kind of obvious isn’t it? All of your choices get a lot easier when you realize they’re made in a VUCA context (i.e. many of them are going to be dead wrong). Your moves get a lot smaller. You’re more humble. You pay attention to the results a lot more. As a simple example, delaying the freezing of decisions prematurely is crucial to a successful transformation. Consider that virtually every decision you make along the way may be open to change. How ironic is it then that most change management frameworks such as Kotter or ADKAR (if they’re used at all) are routinely executed in a linear waterfall manner? The mind boggles.

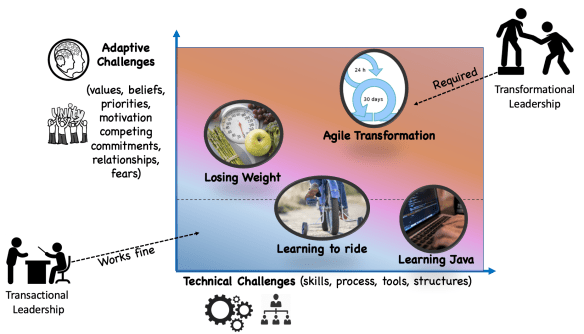

- Most of the hard challenges are adaptive: The Harvard research psychologist Robert Kegan opened my eyes to the concept of adaptive challenges in his book Immunity to Change. Ken Wilbur’s Integral Theory has helped too. Far more than half of the challenges limiting the success of transformations are adaptive in nature rather than technical. They’re invisible to us. Accessing them can be hard but the concept is more simple than you might imagine. Most people I’ve shared this with quickly grasp the importance of paying attention to the adaptive side of the equation. It doesn’t require a lot of theory or explanation. We openly discuss them daily. I find often a brief exercise and simple picture (see below) will do. After they get the idea, they start to see the challenges and the opportunities everywhere. It enables conversations that are impossible without this understanding. Everyone involved needs to know the difference, why it’s important, and learn to see and cope with the difference. Otherwise, you’re blind to more than half the problems and opportunities. In my opinion it’s not culture or uninformed leadership that’s the biggest barrier to change; it’s the failure to grasp this fundamental concept. It’s what I pay attention to most in my practice and it changes everything.

- Adaptive Challenges Require Level-2 Relationships: Adaptive challenges are deeply personal in nature and can not be overcome operating in level-1 relationships; level-2 leadership and relationships are required. Everyone effectively leading change must learn to foster and operate at level-2. In transformational change, this is not optional. My first act as a coach is to move to a level-2 relationships as quickly as possible. This is probably the greatest value an effective coach can bring to an organization; the ability to show up operating from level-2. The impact of just modeling the behavior is like a super power. But it’s not enough for just the coaches to operate at level-2. The more leaders and individual contributors who can operate at level-2, the better the results. It’s that simple.

- Job 2 is more important than Job 1: I learned about Job 1 and Job 2 from Robert Kegan in Immunity to change. When we show up at work we have two jobs: Job 1 is obvious; it’s the content of the conversation; the stuff we think we’re talking about. Also present is Job 2; the thought and energy we put into saving our asses. When I work with clients now half of my focus is what’s happening in service to Job 2 and not just for them but for me too. Learning to see this, helping others notice it, and deciding what to do about it is crucial to successful transformation. If you’re focusing on Job 1 when Job 2 is the problem, you’re just making things worse. I’ll have a lot to say about this in later journals.

The following practices are based on the underlying ‘germ theory’ of Agile transformation and will be expanded on further in later journals.

- Transform, don’t Adopt: Agile transformation is to Agile adoption what losing weight is to following a diet. It’s not that you don’t use a diet, you have to start somewhere, but if your goal is to truly help your client (vs. collecting a fat paycheck) whenever possible help your clients pursue transformation over adoption. Focus on results and be prepared for the complexity of that. Make sure everyone involved knows the difference.

- Start with leadership, not teams: Senior and mid-level leaders, not teams, control and have the most influence over both the technical and adaptive dimensions of changing landscape. Whenever possible, partner with, educate, and coach them to lead from a transformational stance (vs. transactional) to help incrementally create the conditions required for the transformation to succeed. The research behind the book ‘Accelerate’ has made the compelling case that Transformational Leadership and a climate of learning is the foundation for successful Agile / DevOps transformations. Without it, the best you can hope for is somewhat less painful Agile adoption.

- Partner with your client – The old model of medical care was the doctor as expert with tragic results. When things get serious, the best physicians enter into a partnership with their patients. It’s no different for coaches in an Agile transformations. The book Flawless Consulting by Pet Block opened my eye to this in a big way. If you are able to operate as a partner with shared responsibilities and respect rather than ‘the expert’ or worse, a ‘pair of hands’ the results are invariably better.

- Respect culture, help with behavior: The roots of culture run far too deep to change them. Most people have an almost toy-like understanding of what ‘culture’ actually is. Even Edgar Schein, who arguably knows more about corporate culture than anyone else alive, focuses on results and behavior. Understanding models like Spiral Dynamics can help but in the day to day, just meet your client where they are, respect their culture, their wisdom, and help them interact in level-2 relationships to change the behaviors they see fit to change in the ways they see fit.

- Stop focusing on ‘Agile’; create a focus on Results, Outcomes, and Capabilities: “Then don’t call it Scrum!” said no customer ever. An over-focus on frameworks alone is probably responsible for more than half the failed transformations out there. Fewer than half the experts I interview can even begin to clearly articulate the results and outcomes that justify the activities they promote. Regardless of the frameworks your client chooses to use, help them discover and focus on the results, outcomes and capabilities they most need to reach their goals. I shared the approach I use to do this at the Agile 2016 conference. It’s a core part of my practice now. The book Accelerate is a great source for some of these. Modern Agile is another. Help them make these visible, and inspect and adapt their progress frequently. In a VUCA world, adaptation and incremental learning are the key to success.

- Stop Selling Shoes and focus on happy feet – Would you go to a doctor who shoved the same prescription into the hand of every patient who came to her? Or would your rather go to a doctor who really listened to your problem, considered your lifestyle and needs, and then took their time to actively work with you to find a solution that worked for YOU? To cram another analogy into this, there are far too many Prince Charmings out there trying to force fit a shoe that fit Cindella perfectly onto every foot they can get their hands on no matter how much it hurts. It’s horrifying bordering on unethical. If you want a transformation to succeed, you need to treat every client as unique with their own needs and priorities. Remember that context is king, helping comes first, and avoid at all costs doing harm.

Successful Treatment Requires An Understanding of the Underlying Problems

There is so much opportunity to help our clients. As professionals, we need to do less harm.

Like a doctor treating a wound, those of us in the business of change need a deeper and more fundamental understanding of the forces at work limiting change. The current level of practice is far too superficial and over focused on the technical challenges (easy) at the expense of the adaptive (hard). We need a way to start talking about, thinking about, and acting on these VUCA forces in an iterative and adaptive way in partnership with our clients. We need to understand it. So do our clients.

What I’ve listed here isn’t quite that ‘germ theory’ of Agile transformation yet but it’s a start. Some of the bones are there. I’ve listed some of the aspects and learning that have arisen from its application. I’ll share some of my experiences and learning pursuing this in later journals.

I need to acknowledge too that none of these elements by themselves are original with me and I owe a deep debt to my many mentors, muses, and guides along my journey (I promise to enumerate them and their contributions soon). I do believe I’m on the verge of synthesizing these into a useful whole that anyone in the business of Agile Transformation can put to use in practical ways. My hope is to simplify and share this learning in a way that almost anyone can understand and can shave years off of the journey for others.

In the meantime,

Help!

I’m actively seeking collaboration with and support from those who I think of as members of the ‘Agile Dark Web’; those individuals who

- Aren’t afraid of radical ideas and, ideally, are often the source of them

- want to stop the madness and the harm inflicted in the name of ‘Agile’ or ‘agility’

- seek to help and never harm; focusing on their clients needs without ignoring their own

- respect the wisdom and creativity of their clients

- believe our purpose is to help people do their very best work

- believe context is king; that there is no ‘one true way’ thus,

- have no strong allegiance to or passion around any particular framework

- are unfettered by dogma and are willing to discard even closely held beliefs if a better way is found

- are far enough along the Dunning Kruger curve to have obtained a state of humble competence and know there’s still so much to learn

- are willing to contribute to this body of work in service to the larger community who share these same values

If that describes you or someone you know, please reach out to me on the DFW Agile Dark Web

Humbling consulting and trying to figure this stuff out, J.